On otherness

and acquiring a language

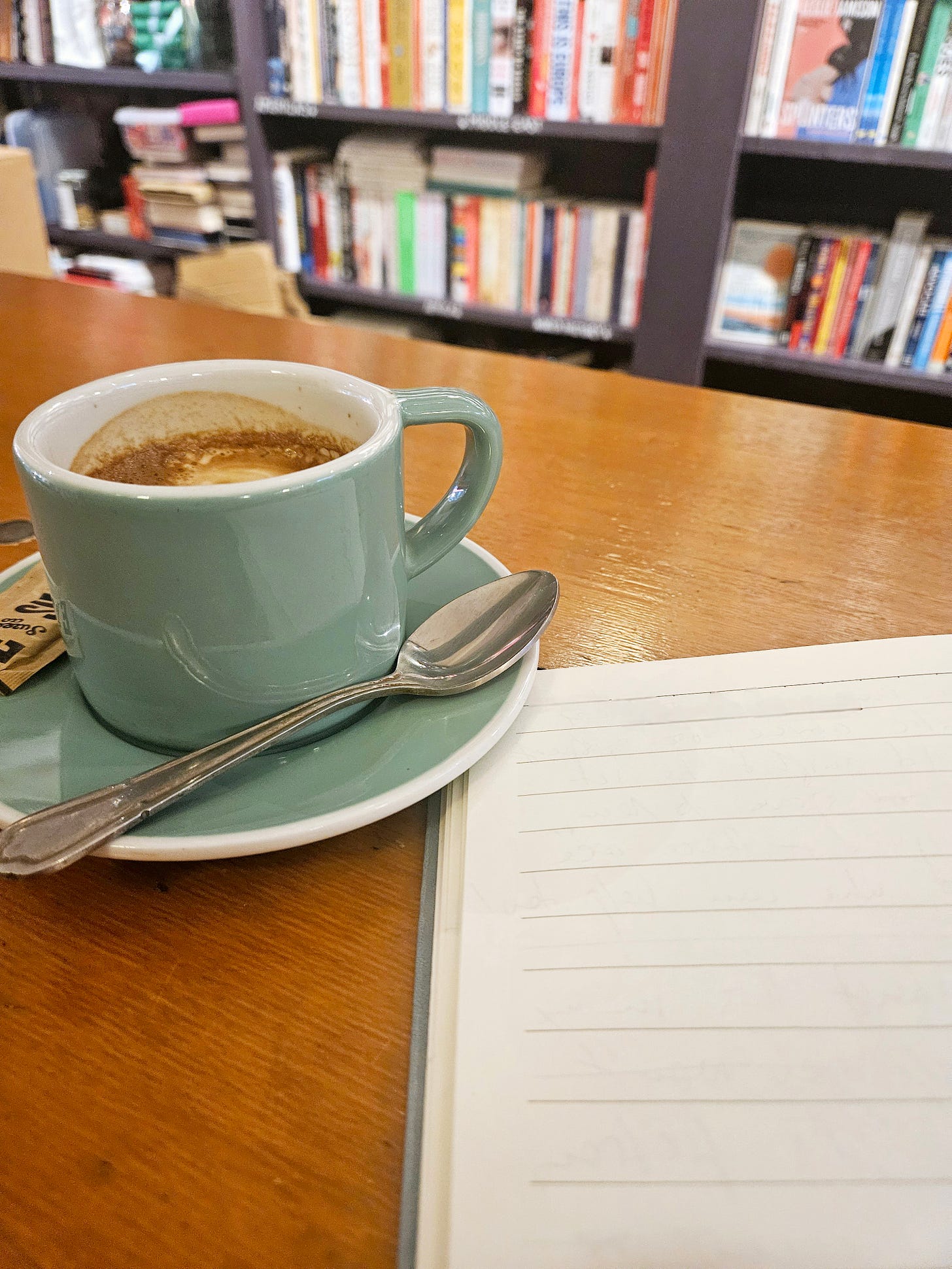

On a murky Wednesday afternoon, as I’m sitting at the large wooden table at BookBar in North London, easing myself into writing and sipping from the aromatic cortado, I let my thoughts meander. Usually, I start writing with a formed topic, a clear structure in mind. But today I decide – not decide, I just let myself abandon the rigidness of my planning process and see what happens.

Fragments of conversation float over from the bookshop, mingling with the faint tunes played in the background that seem both present and not present, like the stranger sharing my table. He takes his coffee slowly while reading a book, close enough that we occupy the same slice of afternoon yet separated by the invisible membrane of our respective solitudes. It's comfortable, this parallel existence within our own confines.

When I think of boundaries (and crossing them), my first thoughts sway towards the physical boundaries defining a country – the country of my childhood, which I left over twenty years ago, before settling in London.

At the time, I viewed my immigration as the physical act of travelling abroad, establishing a new life in an unfamiliar city in a foreign land which I knew only through the filtered lens of books and films.

Of course, it was more complex than that. It wasn't just space I was crossing through. It was a temporal shift as well, moving from childhood and adolescence into adulthood.

Those first months, those first years really, I found myself inept at untangling the social and cultural cues of this new place, as if everyone was speaking in code. It wasn't just a new language I had to learn to be able to fully and eloquently express myself; I had to learn the grammar of an entire culture.

I had to diffuse my authentic self – my mother tongue, my inherited ways of being – into the expectations of British society – at the workplace, in social interactions, while consuming information and media content. I was always translating myself.

Nourishing my identity with newly acquired way of being was imperative for my survival and even existence.

The very act of occupying the liminal space where my mother tongue and the adoptive language intersected and punctuated my identity, was adding layer upon layer of otherness and belonging at the same time.

But I was never interested in engaging with the concept of otherness from an exile point of view. Instead, I've been exploring culture and language in a way that's been an enriching experience, opening up opportunities of experimentation and playfulness.

I wrote my second novel Arrival in English, which was a fascinating process, and since then, I've been mainly writing in English. My craft became liberated from the structures that were scaffolding my craft when I was looking for refuge in the safety of my mother tongue.

Instead, I began experimenting with the concept of bilingual writing – not a translation of words and sentences, but of ideas, concepts and cultural identities.

British-Turkish writer Elif Shafak wrote:

"Writing in another language gives me an additional freedom, an additional way of thinking. It's a challenge, but I like the challenge".

I find so many similarities between the way we feel about identity, writing in or adoptive language and migration.

My linguistic makeup will always be a part of me, and of course, it will betray the duality in my cultural identity, this strange hyphenated existence – Bulgarian-British, neither purely one nor the other.

But I no longer feel restricted by this. Instead, I'm learning to hold both identities like two halves of a fruit, sweet with possibility. In the end, otherness isn't opposition but abundance: for me, it’s become this expensive feeling of being multiple, of containing multitudes.

I finish my cortado, now cold. The stranger gathers his things and leaves, taking his portion of our shared solitude with him. Outside, the city grows loud with conversations in all its languages, in all its voices.

Until next time,

Nataliya x